http://globaleconomicanalysis.blogspot.com/2013/02/500000-people-sign-petition-asking.html

As I have said repeatedly, one never knows when the tipping point is. However, given the combination of massive government corruption coupled with unemployment of 26.6% and youth unemployment of 56%, it is certain the tipping point will indeed be reached.

For more on the scandal and what the prime minister is doing to suppress reporting of the corruption, please see Big Brother in Action: EU Wants Power to Sack Journalists; Prime Minister Rajoy Threatens Newspapers Following Corruption Articles.

Mike "Mish" Shedlock

http://www.acting-man.com/?p=21578

As we have pointed out recently, France is the only major country in Europe in which the free-fall in PMI data has merrily continued to accelerate. Mr. Hollande needs to absorb the lesson that capital moves to wherever it is treated best. Entrepreneurs are not likely to wait around to be robbed of the fruits of their efforts. Instead they will decamp and continue their efforts elsewhere. We should however add here that 'capital flight' is really a bit of a misnomer; it is more accurate to speak of a large scale revaluation of capital.

Ludwig von Mises describes the process in Human Action:

http://www.zerohedge.com/news/2013-02-01/italian-bank-scandal-spreads-other-banks-berlusconi-big-winner

Friday, February 01, 2013 6:09 PM

500,000 People Sign Petition Asking Prime Minister Rajoy to Resign

The indignation of citizens over payouts and graft in Spain is highlighted by a flood of protests on Spanish social networks. A campaign on Change.org, a platform with 25 million registered has collected a record 500,000 signatures calling for the resignation of Prime Minister Marinao Rajoy.

Via Google translate from El Pais, please consider 500,000 People Sign Petition Asking Prime Minister Rajoy to Resign.

Via Google translate from El Pais, please consider 500,000 People Sign Petition Asking Prime Minister Rajoy to Resign.

The indignation of the public by publication in the country of the secret papers of the PP extesoreros, reflecting payments to the party leadership, is flooding social networks with messages calling responsibilities to Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy. appear together under tags like # Rajoydimisión or # quesevayantodos , in addition to the proposal for this diary # lospapelesdebárcena s. This wave of criticism also translates into hundreds of thousands of citizens (over 500,000 in just over a day) have signed a petition asking for "the resignation of the leadership of the PP", including Rajoy, and "all who have received payments in black money ".

"I wish we lived in a democracy and could revoke the government for not fulfilling its election and alleged corruption cases like this," explains Pablo Gallego , petition drives the platform Change.org . This 24 year old from Cadiz that their initiative is collecting 40,000 signatures per hour, a pace that, if continued throughout the day, could mean reaching one million accessions this Saturday.Tipping Point

If that number is reached, Gallego with messages intended to go to the national headquarters of the PP in Madrid.

As I have said repeatedly, one never knows when the tipping point is. However, given the combination of massive government corruption coupled with unemployment of 26.6% and youth unemployment of 56%, it is certain the tipping point will indeed be reached.

For more on the scandal and what the prime minister is doing to suppress reporting of the corruption, please see Big Brother in Action: EU Wants Power to Sack Journalists; Prime Minister Rajoy Threatens Newspapers Following Corruption Articles.

Mike "Mish" Shedlock

http://www.acting-man.com/?p=21578

An Inadvertent Admission

To the surprise of the socialist enarques ruling France these days, it has turned out that the country is not exempt from the laws of economics. Imagine that!

First labor minister Michel Sapin let it slip that France is 'totally bankrupt', which probably isn't news for readers of this blog. France is of course not the only nation that finds itself in this predicament. Nearly all the welfare/warfare states of the industrialized West are bankrupt if we properly consider their balance sheets. Sapin's inadvertent admission has been extensively discussed elsewhere already, so we at first didn't write about it, but we decided that it deserves at least a brief mention.

Naturally the minister of finance, Pierre Moscovici judged the remark 'inappropriate'. High ranking politicians are not supposed to blurt out the truth. According to Moscovici:

“France is a really solvent country. France is a really credible country, France is a country that is starting to recover.”

Right-o. And in other news, Pater Tenebrarum has been appointed emperor of China.

“Going Galt”

Then it became known, via data published by the Bank of France, that so-called capital flight from France has accelerated markedly in recent months (this is reflected in a sharply growing TARGET-2 liability). This is what happens when punitive tax rates are instituted and the government practically denounces anyone protesting its wealth grab as a 'traitor'. According to the Telegraph:

“Fresh data from the Banque de France show a sudden rise in outflows in October and November, registered in the so-called Target2 payments system of the European Central Bank.Simon Ward from Henderson Global Investors said the net loss of funds was €53bn (£43.8bn) over the two months, roughly the period when Mr Holland unveiled a string of tax rises and suffered a collapse in relations with French business.A key gauge of the French money supply — six-month real M1 — has been contracting at an accelerating rate ever since Mr Holland's election in May. It has fallen to levels last seen in the depths of the crisis in 2008.France's money data is now flashing more serious warnings than numbers in Italy or Spain. "Taken together, it is clear that there has been a major loss of confidence and funds have been pulling money out of the country," said Mr Ward.While France is at no serious risk of a debt crisis, it has been bumping along at slump levels for two years with the youth jobless rate rising to a record 27pc.”

(emphasis added)

France may not be at a 'serious risk of a debt crisis' right now, but by now it should be obvious how utterly meaningless such assertions are. After all, credit default swap spreads on Greece's sovereign debt traded at 35 basis points in 2007. It sure wasn't judged to be at 'serious risk of default' by the markets at the time. In the meantime it has actually defaulted twice in a row, and a third default is all but assured. Prior to the first debt restructuring, its CDS spreads went out at 26,800 basis points.

France's 10 year government bond yield remains very low. As of yet, it does not signal much worry on the part of investors. That may however change at some point – click for better resolution.

5 year CDS on the government debt of Ireland, Japan, Belgium and France (the orange line). At 85.3 basis points, CDS on France are still way below their highs seen at the height of the euro debt crisis panic. However, for an industrialized 'core' country of the euro area, this is quite an elevated level actually – click for better resolution.

The Telegraph reports further that businessmen are now increasingly 'going Galt' in France in protest over the socialists' anti-free market campaign:

“Mr Hollande's `soak-the-rich' campaign and a 75pc millionaire tax has erupted into controversy since comedianGérard Depardieu renounced French citizenship and decamped to Russia in protest, egged on Brigitte Bardot.

Yet the bitter stand-off between France's Socialist leader and French business is a greater concern. An alliance of private sector groups issued a "State of Emergency" alert in October. The employers group MEDEF said business was "in revolt across the country", warning that bankruptcies were accelerating and firms were slashing investment.

"Large foreign investors are shunning France altogether," it said.

Mr Hollande has sought to rein in his industry minister Arnaud Montebourg, who first lashed out at the Peugeot family and then threatened to nationalize ArcelorMittal's steel operations in Lorraine, describing Lakshmi Mittal as "unwelcome" in France.”

A Revaluation of Capital

As we have pointed out recently, France is the only major country in Europe in which the free-fall in PMI data has merrily continued to accelerate. Mr. Hollande needs to absorb the lesson that capital moves to wherever it is treated best. Entrepreneurs are not likely to wait around to be robbed of the fruits of their efforts. Instead they will decamp and continue their efforts elsewhere. We should however add here that 'capital flight' is really a bit of a misnomer; it is more accurate to speak of a large scale revaluation of capital.

Ludwig von Mises describes the process in Human Action:

“The mobility of the investor manifests itself in the phenomenon called capital flight. Individual investors can go away from investments which they consider unsafe provided that they are ready to take the loss already discounted by the market. Thus they can protect themselves against anticipated further losses and shift them to people who are less realistic in their appraisal of the future prices of the goods concerned. Capital flight does not withdraw inconvertible capital goods from the lines of their investment. It consists merely in a change of ownership.It makes no difference in this regard whether the capitalist "flees" into another domestic investment or into a foreign investment. One of the main objectives of foreign exchange control is to prevent capital flight into foreign countries. However, foreign exchange control only succeeds in preventing the owners of domestic investments from restricting their losses by exchanging in time a domestic investment they consider unsafe for a foreign investment they consider safer.If all or certain classes of domestic investment are threatened by partial or total expropriation, the market discounts the unfavorable consequences of this policy by an adequate change in their prices. When this happens, it is too late to resort to flight in order to avoid being victimized. Only those investors can come off with a small loss who are keen enough to forecast the disaster at a time when the majority is still unaware of its approach and its significance.Whatever the various capitalists and entrepreneurs may do, they can never make mobile and transferable inconvertible capital goods. While this, at least, is admitted by and large with regard to fixed capital, it is denied with regard to circulating capital. It is asserted that a businessman can export products and fail to re-import the proceeds. People do not see that an enterprise cannot continue its operations when deprived of its circulating capital. If a businessman exports his own funds employed for the current purchase of raw materials, labor, and other essential requirements, he must replace them by funds borrowed. The grain of truth in the fable of the mobility of circulating capital is the fact that it is possible for an investor to avoid losses menacing his circulating capital independently of the avoidance of such losses menacing his fixed capital. However, the process of capital flight is in both instances the same. It is a change in the person of the investor. The investment itself is not affected; the capital concerned does not emigrate.”

(emphasis added)In short, what is happening in France is a 'flight of deposit money' on the one hand, and a downward revision in the value of its capital stock on the other. Given that entrepreneurs are threatened both by expropriation (as the Arcelor-Mittal case as well as the Peugeot case showed) and the fact that a large portion of their profits will be confiscated, the value of capital in France obviously declines so as to reflect these threats.The sellers are removing the proceeds from the government's reach by sending them abroad. The buyers are hoping that the socialist ideologues will eventually change their stripes and that the purchase prices already discount the dangers adequately. That may be a miscalculation, but of course we don't know the future; after all, Mitterand's most disastrous socialist policy measures were eventually also reversed.

http://www.zerohedge.com/news/2013-02-01/italian-bank-scandal-spreads-other-banks-berlusconi-big-winner

Italian Bank Scandal Spreads To Other Banks: Berlusconi Big Winner

Submitted by Tyler Durden on 02/01/2013 09:34 -0500

As we warned last week when the BMPS fraud story broke, this is highly likely to be the canary in the Italian banking system coalmine; and sure enough today, Reuters reports that:

- ITALIAN PROSECUTORS INVESTIGATING MONTE PASCHI, BNL, UNICREDIT, INTESA SAN PAOLO

AND CREDEM - JUDICIAL SOURCE

Italian bank stocks (still under short-selling bans) are plunging (and the EUR is dropping) but, as Reuters notes, the winner in this growing debacle is Berlusconi as Italians blame the Democratic Party for the problems at the banks. Most pollsters, however, still think it unlikely that Berlusconi can overtake Bersani with little more than three weeks to go - after being more than 15 points behind in early December. And just as a reminder Mario Draghi was running the Bank of Italy during this era of evasion.

Today in Italian Banks...

and YTD...

and Spain slowly unwrapping scandal.......

http://elpais.com/elpais/2013/01/29/inenglish/1359465410_485035.html

What lies inside Bárcenas' boxes?

The judicial net is closing around the former PP treasurer

The question worrying many is exactly what will he reveal about his party's finances

On January 16 Swiss officials reported they had found accounts containing 22 million euros registered to Luis Bárcenas, the former treasurer of the ruling Popular Party (PP). Appointed by PP leader Mariano Rajoy in 2008, Bárcenas was forced to resign a year later for his possible role in another major corruption scandal, known as the Gürtel case. Bárcenas has denied any wrongdoing, saying he was holding the money for investors.

Then, on January 21, Jorge Trías, a former PP member of parliament, published an article in EL PAÍS accusing Bárcenas of regularly handing out envelopes containing as much as 10,000 euros in cash to other high-ranking PP officials. "Outside of whatever the prosecutors and judges do," wrote Trías, "the Popular Party must explain in complete detail what means it has used to finance itself."

Last week, Spanish daily El Mundo published an article suggesting that many of the officials who received kickbacks signed receipts for the payments. And Bárcenas has also claimed that, after years of holding the Swiss accounts without declaring their contents to Spanish tax authorities, he registered and paid reduced taxes on half the amount in 2012 thanks to a fiscal amnesty passed by the PP - which by then had been elected to run the government.

So how exactly did Bárcenas come by 22 million euros? "Luis is clever and has made money," says Ángel Sanchís, also a former PP treasurer, who made his fortune in banking before entering politics in 1978. When Bárcenas opened the account in Switzerland he claimed to be involved in Sanchís's fruit empire in Argentina, La Moraleja. "It is completely false," says Sanchís. "He has admitted he did it to make a big noise. All he gave me was authorization to access his account information to assess his investments. He always thought of himself as a good stock market player. And he made money."

However, a transaction for three million euros to Bárcenas' account from Brixco, a client of Sanchís, raised questions about possible bribes by Gürtel corruption network ringleader Francisco Correa. Sanchís denies this: "I put him in touch with Brixco and it seems it extended a credit line, a commercial credit between two companies. It is a clear and transparent operation."

The judge investigating Gürtel has asked police analysts to listen to a wire tap in which a man admits to bribing Bárcenas with around six million euros, to determine if the voice belongs to Correa. The recording device was hidden for two years in the pocket of former PP councilor José Luis Peñas, who uncovered the largest corruption network in Spain since the return to democracy. Dozens of high-ranking PP officials feature on the recordings, with the name of Bárcenas cropping up abundantly.

Bárcenas is taking no chances. On Saturday July 4, 2009, he took away nine boxes filled with documents from his office in party headquarters in central Madrid and drove them by car to his nearby apartment.

Bárcenas, who was the PP senator for the northern region of Cantabria, had occupied senior posts in the party for much of the previous two decades, and had been appointed treasurer the year before. But five months earlier, Supreme Court judge Baltasar Garzón had launched Operation Gürtel, an investigation into a kickbacks-for-contracts scam that implicated many senior Popular Party figures, including Bárcenas, who was about to be called to face charges of money laundering and fraud. Those boxes contained many secrets about the party's finances.

Heads had already rolled by then: mayors and councilors had been forced to stand down while awaiting trial. In two weeks, the head of the regional government of Valencia, Francisco Camps, would resign ahead of his trial.

But Bárcenas had stood his ground, despite police and tax office accusations that he was the kingpin in the Gürtel network, the man referred to in documents as LB or LBG, as well as "Luis the Bastard." The treasurer stands accused of receiving hundreds of thousands of euros in illegal commissions in return for favors.

For the moment, party leader Mariano Rajoy has stood by Bárcenas, publicly defending him and refuting the accusations. But time is running out.

Bárcenas is angry with the party to which he has dedicated the past 20 years of his life and feels the leadership has let him down, telling one colleague at the time: "I am being treated worse than Camps, and it should be the other way round, because I know things that Camps could never know about, and I have protected a lot of people over the years."

Behind the complaints of ingratitude lies the implicit threat that Bárcenas will reveal the contents of the nine boxes he took from PP headquarters.

Three weeks later, on July 23, Bárcenas appeared before a Supreme Court judge. When Francisco Camps had been called to testify he had been accompanied by several senior PP figures in a show of solidarity; but nobody showed up at Bárcenas' hearing.

A few days afterwards, Bárcenas stepped down as party treasurer and went on vacation. The break with the party had begun.

Eight months later, in April 2010, Bárcenas resigned his seat as senator, and left the party, saying he wanted to focus on his defense. Until then, the party had paid for his legal costs, but now he had to pay for them himself. He also lost his 200,000-euro-a-year salary from the party.

Spotlight on PP finances

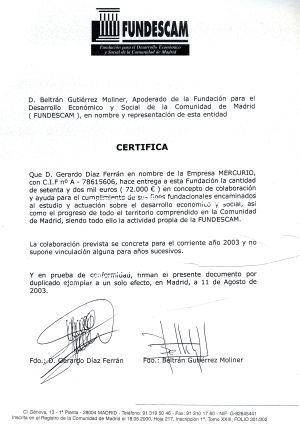

The judge's summary of the Gürtel case includes documents in the possession of the Popular Party (PP) about donations to Fundescam, a Madrid party foundation that allegedly financed election campaign events, which is forbidden by law. These include documents detailing money handed over by the disgraced former president of the CEOE employers' organization Gerardo Díaz Ferrán (above). As the alleged offenses took place nine years ago, they are now subject to the statute of limitations. The PP also stands accused of receiving donations from well-known business leaders who wrote dozens of checks, each for amounts below 3,000 euros, thus avoiding the need to declare them to the Audit Office. Luis Bárcenas would have known about these practices, and will likely have evidence of them. There are also documents showing that during the October 2004 election campaign the Madrid regional government used money from the PP-run FAES think-tank to pay for campaign meetings. Using foundation funds to pay for party rallies is considered illegal financing.

As the Supreme Court investigation rolled on, new evidence emerged against the former treasurer: money borrowed to buy works of art that he explained was a loan to his friend Rosendo Naseiro; references in documents seized by police that point to his involvement in money laundering; and the half-a-million euros his wife, who has no job or income, deposited in an account in 2006.

But the party hadn't abandoned him completely: even as the evidence against him continued to mount, the PP allowed him to use his official car, and secretary, as well as providing him with an office and allowing him to access documents stored at party headquarters.

By now Bárcenas had taken to showing colleagues documents that revealed how senior party figures used their position to enrich themselves; there are others that implicate organizations linked to the party of misappropriating donations from leading business figures.

The Popular Party receives around 10 times the amount of donations the Socialist Party does, and for the last two decades Bárcenas has counted every penny it has been given. And as the judicial net closes around him, he has begun to remind colleagues that he might find it difficult to explain the party's accounting procedures to the authorities.

The Madrid High Court was also on the PP's money trail. The party's FAES think-tank received anonymous donations from well-known business leaders, among them the disgraced former head of the CEOE employers' confederation, Gerardo Díaz Ferrán. The court suspected these donations were used to pay for election campaign meetings in 2003 for Esperanza Aguirre, the then head of the Madrid regional government, organized by bogus companies within the so-called Gürtel network, and shown in their accounts, but which cannot be investigated under the statute of limitations.

At the same time, the defendants on trial in Valencia for their alleged involvement in the Gürtel network pointed the finger at Bárcenas, who rejected the accusations, again blaming party leaders for failing to back him up.

Bárcenas circulated photocopies of the dozens of checks made out to the bearer signed by leading business figures. As they are all for amounts below 3,000 euros, regional party leaders were not legally required to declare them to the Audit Office.

Bárcenas has since told colleagues at PP central office that he has evidence that the anonymous donations were used to bolster the salaries of senior party figures, who were given brown envelopes filled with cash each month - money that they did not declare to the tax office.

Over the course of 2011, the judicial investigation would grind on, ever more slowly, and Gürtel would gradually slip from the headlines. The corruption allegations did not damage the PP's vote, and the party's showing in the opinion polls continued to improve in the run-up to the November 2011 general elections, which it won by a landslide.

In the second half of 2011, Bárcenas' fortunes improved. The Madrid High Court judge overseeing the investigation ruled there was not enough evidence against Bárcenas to bring charges and closed the case, despite not having received the results of an investigation into overseas accounts, among them several in Switzerland, to determine whether the PP's former treasurer had stashed money in secret, offshore, accounts.

By September, for the first time in two-and-a-half years, Bárcenas had grounds for optimism: the case against him had been closed, and the PP was set to win the upcoming elections. But within three months, Bárcenas was back in trouble with the courts.

In December, anti-corruption investigators and the public prosecutor successfully appealed against the Madrid High Court's decision to close the case against Bárcenas.

Investigating magistrate Pablo Ruz questioned Bárcenas about the purchase of art works, and requested the results of investigations into overseas accounts. Bárcenas told the judge that he was the victim of a witch hunt, and that the police, the public prosecutor and the courts were all out to get him. At the end of December, Bárcenas learned that the authorities had discovered an account in Switzerland in the name of a Panamanian-registered company with 22 million euros in it.

The news wasn't made public until the new year, when Judge Ruz asked for further documentation about Bárcenas' Swiss bank accounts. At this point, part of the contents of the boxes that Bárcenas took from PP headquarters was leaked to the press. El Mundo published a story about the undeclared payments to senior PP figures, but said Rajoy and party secretary general María Dolores de Cospedal were not involved.

Senior PP leaders say Bárcenas did not want to break the story about the payments, knowing that this would hurt the few senior figures left in the PP who still supported him. Bárcenas has stated that he remains loyal to Rajoy. He believes that Cospedal is behind his downfall.

Bárcenas and his supporters accuse Cospedal of leaking information about the secret payments, inadvertently relieving him of the burden of having to do so. Cospedal and her supporters deny the accusation and say Rajoy knows who is behind the leaks.

Bárcenas' enemies know that as the former treasurer of the party currently in government, he has enough information about its finances to damage everybody, from the prime minister down.

For two decades Bárcenas has played a direct role in the financing of the PP. The party's accounts may have been approved by the Audit Office, which is five years behind in its inspection of the country's political parties, but Bárcenas knows the ins and outs of donations that sources close to him say were never officially recorded.

Bárcenas could recover his memory and reveal who financed election campaigns, or identify donations to the party that were never accounted for, say those close to him.

The former treasurer has kept quiet so far, seeking to avoid a permanent break with the party. He would prefer not to destroy the PP by revealing his vast inside knowledge of its financing, say those who know him.

They also point out that contrary to the widely held belief that he was involved in the Gürtel network, he stood up to Francisco Correa, the man behind the kickbacks-for-contracts scandal, back in 2004, when Mariano Rajoy took over the PP leadership. Along with his predecessor as treasurer, Álvaro Lapuerta, he warned Rajoy about Correa's involvement in a multi-million-euro rezoning deal in the Madrid district of Arganda involving senior figures in the regional government, led at the time by Esperanza Aguirre.

Aguirre chose to ignore the warning, rejecting Bárcenas' suspicions. The High Court is still investigating possible irregularities, and whether illegal commissions were paid by property developers Martinsa, a group that subsequently went spectacularly bankrupt.

At the same time, the party distanced itself from the Gürtel network thanks to Lapuerta and Bárcenas, who refused to allow Correa and his associates to sully the PP's name for their own short-term financial gain. Bárcenas might have hoped the case would go away when last February, Spain's Supreme Court found Judge Baltasar Garzón guilty of illegally ordering wiretaps to monitor conversations between several defendants in the Gürtel case and their attorneys, and barred him from the judiciary for 11 years, but new evidence continues to emerge.

Four years after Gürtel was uncovered, questioning the honesty of Rajoy and the party's leadership, Bárcenas continues to face charges. The PP, which, like Bárcenas, believed it was out of the woods after its landslide victory in 2011, is now fearful that its former treasurer's Swiss bank accounts will taint it once again, and undermine its credibility at a time when it is imposing unprecedented, and unpopular, austerity measures while doing nothing to improve the economy or generate jobs. The question now is whether Bárcenas will tip the balance by revealing all he knows about the PP's finances.

http://elpais.com/elpais/2013/02/01/inenglish/1359735052_413271.html

Most donations recorded on PP slush fund ledgers are illegal

Over two-thirds of funds received from business and private patrons were outside of the law

A significant portion of the donations recorded in the handwritten ledgers secretly maintained by Luis Bárcenas, the former treasurer for the ruling Popular Party (PP), violated party financing legislation.

Over two-thirds of the alleged donations in these parallel accounts, which EL PAÍS brought to light on Thursday, could never have been made through official channels, either because they went over the 60,000-euro limit or because they were made by individuals or businesses that were barred from being donors.

On the expense side, the ledgers show regular payouts to members of the PP executive, who allegedly accepted this undeclared money on top of their official salaries.

The evidence suggests illegal party funding, although the PP is denying it.

The party finance legislation in force between 1987 and July 2007 said that “parties may not receive, either directly or indirectly, contributions from the same person or legal entity above the amount of 10,000,000 pesetas [60,101 euros] a year. Also forbidden are contributions from companies with current contracts to provide services or perform work or be a supplier to any public agency.”

But the notes found on Bárcenas’ secret accounts show systematic violations of this norm. There are single contributions of up to 250,000 euros, and in one case the same individual donated 400,000 in one year. The legal limit was surpassed on more than 30 occasions (the limit was raised to 100,000 euros in mid-2007).

Most of the donors who show up on the books are individual tycoons and companies from the construction sector, as well as regular recipients of government contracts. EL PAÍS got in touch with some of these donors, who all denied any involvement. In some cases, the identity of the people on Bárcenas’ list is clear; in others, there is only a first name or a surname.

Juan Miguel Villar Mir, chairman of OHL, and Luis del Rivero, former chairman of Sacyr Vallehermoso, are perhaps the best-known construction magnates on the list. Both categorically denied having donated 530,000 euros and 480,000 euros, as shown on the handwritten ledgers.

Yet even they are not the most generous donors on the list. The top position goes to José Luis Sánchez (who is sometimes listed with his full name and others simply as J. L. Sánchez or José Luis). Over the course of five years, this person gave the party 1.15 million euros. So who is he? The individual in question could be the Málaga developer José Luis Sánchez Domínguez, founder and president of the Sando Group.

The second most generous donor is Manuel Contreras (sometimes listed as M. Contreras), with close to a million euros. Contreras is head of AZVI, a family-run construction group from Andalusia.

There are also several gifts by people who are involved in the Gürtel kickbacks-for-contracts scheme, including Pablo Crespo, Juan Cotino (head of Sedesa) and Alfonso García Pozuelo (Construcciones Hispánica). Bárcenas himself had to resign in 2009 due to his links to the corruption case.

Other donors are harder to identify, such as “López H.” who gave 15 million pesetas (90,150 euros) in 1997. The following year, there was another four-million-peseta donation by one “López Hierro.” EL PAÍS got in touch with the husband of PP secretary general Dolores de Cospedal, whose name is Ignacio López del Hierro and who has sat on the board of real estate firms like Bami or Metrovacesa.

López del Hierro categorically denied being the person on the list, and stated that he never gave money to the PP. He also noted that back then, he was still not with Bami, and was instead an executive at ONCE, the blind persons’ association; he stressed as well that he had no links to the PP and had not yet met his future wife.

The fine for accepting donations over the legal limit or from banned sources was, until 2007, twice the amount of the donation. That earlier law also stipulated that all donations should be made into bank accounts opened specifically for that purpose. From that point of view, all of the donations on Bárcenas’ secret accounts would be illegal, as handwritten notes repeatedly specify that all donations were made in cash.

At the height of the slush-fund system, Bárcenas’ box had over 900,000 euros in it. Records show that, once the payouts to PP leaders and other expenses had been met, any remaining money was transferred into an account for donations that the PP kept at Banco de Vitoria (later bought out by Banesto). Around 1.2 million euros were deposited in this account. The other 7.5 million euros were used to pay PP leaders and cover various operational costs.

http://elpais.com/elpais/2013/02/01/inenglish/1359751057_012420.html

Deputy PM says government is “stable” despite party finance scandal

PP barons urge Rajoy to provide “maximum transparency” in wake of slush fund allegations

Aznar files lawsuit against EL PAÍS

EL PAÍS / AGENCIES Madrid 1 FEB 2013 - 21:39 CET

Popular Party (PP) Deputy Prime Minister Soraya Sáenz de Santamaría on Friday came out in defense of the government in the wake of the Bárcenas financing revelations and made assurances that “if we have to toughen measures, we will do so.”

“This government is stable,” she continued. “Firstly because its parliamentary majority is, and secondly because it does what needs to be done.” Over the suggestion that the prime minister had received cash payments on the side, his deputy said: “I have never seen him break a rule. While in government, in opposition, and then in government again, I have always seen in Mariano Rajoy an exemplary conduct, an example of an upright life and one dedicated to public service.”

Rajoy is due to appear at an emergency meeting of the PP’s Executive Committee on Saturday. There he will face the inquisition of leading party figures.

José Antonio Monago, Alberto Núñez Feijóo and Juan Vicente Herrera, regional PP premiers of Extremadura, Galicia and Castilla y León respectively, have called for an internal audit and public explanations to be given greater urgency in the face of the outcry over the matter.

“There must be maximum transparency at this time and [Rajoy] needs to give all the necessary explanations,” said Monago.

Herrera added that the extracts from Bárcenas’ ledgers published by EL PAÍS were not without basis and should be investigated by the courts. “There’s no point in shooting the messenger.”

Former PP Prime Minister José María Aznar on Friday filed a lawsuit in a Madrid court against EL PAÍS for defamation in response to suggestions that he too was paid salary top-ups from a slush fund.

No comments:

Post a Comment