http://globaleconomicanalysis.blogspot.com/2012/08/eurozone-new-business-sinks-at-fastest.html

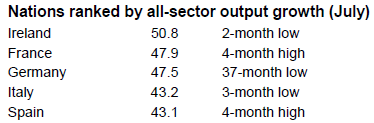

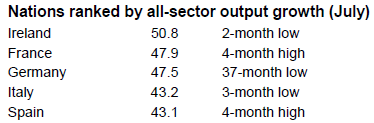

The worst performers by far were Italy and Spain. The rate of contraction in France slowed marginally, while the downturn in Germany was the steepest for over three years.

Summary:

Conditions across Italy’s service sector took a turn for the worse in July, as incoming new business fell at the fastest rate since March 2009. Activity and

employment both dropped as a result, and for the first time since the launch of the survey in January 1998 firms generally expected output to be lower in a year’s time than current levels. Another negative development for businesses was a slight rise input price inflation from June’s seven-month low.

Outstanding business at services firms was further reduced during the latest survey period, extending the current sequence of decline to 17 months. Moreover, the overall rate of depletion quickened to the fastest since September 2009. Weakness in new business inflows was the most frequently cited reason for lower backlogs.

Read more at http://globaleconomicanalysis.blogspot.com/2012/08/eurozone-new-business-sinks-at-fastest.html#PEdSbIDbutkPwB1V.99

Markit reports Stabilisation of French service sector activity during July

Summary:

French service providers reported that business activity was unchanged during July. That followed declines in each of the previous three months. New business and backlogs of work both fell at slower rates, but companies nevertheless made sharper cuts to staffing levels. Competitive pressures led to a further drop in output charges, despite another rise in input costs. Panel members signalled a weaker outlook with regards to future activity, with optimism falling to the lowest level for almost three-and-a-half years.

Manufacturers reported a steeper fall in output during July, with the rate of decline accelerating to the fastest since April 2009. Overall private sector activity was down for the fifth successive month, although the latest drop was the slowest since March.

The level of new business placed with French service providers fell for the fourth month running during July.

Markit Germany Services PMI®

Markit reports Services activity rises slightly, despite sharpest drop in new work since June 2009

Summary:

At 50.3 in July, up slightly from 49.9 in June, the final seasonally adjusted Markit Germany Services Business Activity Index posted back above the neutral 50.0 threshold. However, the latest reading signalled only a fractional expansion of overall business activity, and was well below the long-run survey average (53.0). July data indicated that growth was largely driven by Hotels & Restaurants and Renting & Business Activities.

Markit reports New orders decrease at fastest pace since October 2011

Respondents indicated that falling new business had been the main factor behind the drop in activity. In turn, new orders declined as clients were hesitant to embark on new projects given deteriorating economic conditions. New orders fell at a sharp pace that was the fastest since October 2011.

Companies worked through outstanding business in July as new orders decreased. Backlogs of work were depleted at a substantial pace, and the steepest in seven months.

Service providers continued to lower their staffing levels during July. Employment has now fallen in each of the past 53 months. The rate of job shedding was substantial, and faster than that recorded in June. Of the six monitored sectors, the sharpest fall in employment was posted at Renting & Business Activities companies.

Services companies expect activity to fall over the coming 12 months, the first time this has been the case since May 2009. The forthcoming rise in VAT is forecast to further reduce consumer demand, and therefore business activity.

Eurozone GDP is going to decline rapidly and businesses will shed workers if new orders continue to decline. Let's look at the new orders, expectations, and employment components from the above reports.

Countries struggling to meet budget targets have responded by raising taxes. The result of that stupidity can easily be predicted in advance: economic activity will contract further, causing budget target shortfalls.

Yet, Spain is hiking taxes to appease the bureaucrats in Brussels.

In France, prime minister Francois Hollande is about to Wreck France With Economically Insane Proposal: "Make Layoffs So Expensive For Companies That It's Not Worth It"

I wrote that before socialists took over both houses in French parliament. Many suggested he would not follow through. Unfortunately he has. Please consider my July 16 post Peugeot Has 51% Chance of Debt Default; Hollande Says France Will Not Let Peugeot Lay Off Workers

Hollande is also raising taxes like mad and French businesses are likely to head to the UK and other places in response. Many wealthy have fled the country.

Correct Approach

The correct approach is to reduce taxes and make it easier for businesses to fire workers. Logic dictates that if it's difficult or impossible to fire workers, businesses will not hire them in the first place.

Ass-Backwards Eurozone Policies

Most countries in Europe now have ass-backwards policies in place. The silver lining in this mess is those ass-backwards policies will accelerate the breakup of the eurozone, and that is a good thing.

and.....

http://www.prudentbear.com/index.php/creditbubblebulletinview?art_id=10692

Mr. Weidmann: “...Despite all our various qualifications and tasks, within the Bank, there is a shared vision and a clear commitment to monetary stability. This is unique for such an institution and has also made the Bank an attractive option for people applying to work for us. The public good of maintaining price stability and thus contributing to the common good is a major incentive for many.”

Especially these days, I have little company when it comes to extolling the virtues of the Bundesbank or German economic thinking more generally. For me, it’s an issue of principle. Over the past 22 years I have come to deeply respect the German (including “Austrian”) view of economics, money and Credit, and monetary management. I’m partial to a sound analytical framework, discipline and the so-called “orientation of stability.” Back in 2004, in a CBB titled “Issing vs. Greenspan,” I highlighted a WSJ op-ed by then ECB Chief Economist Otmar Issing, with his prescient warning against central banks ignoring Bubbles:

Saturday, August 04, 2012 11:30 AM

Eurozone New Business Sinks at Fastest Rate in 3 Years; Germany Composite PMI at 37-Month Low; Ass-Backwards Eurozone Policies

With everyone watching and analyzing US jobs data on Friday, there were a number of other news reports showing steeper contractions in much of the world. Let's start off with a look at the rapidly deteriorating eurozone.

Markit Eurozone Composite PMI® – Final Data

Markit reports Eurozone downturn continues at start of Q3 2012

Markit Eurozone Composite PMI® – Final Data

Markit reports Eurozone downturn continues at start of Q3 2012

The Eurozone economy remained in a downturn at the start of Q3 2012. At 46.5 in July, little-changed from 46.4 in June, the Markit Eurozone PMI® Composite Output Index signalled a contraction in output for the tenth time in the past 11 months. The headline index came in slightly above the earlier flash estimate of 46.4.Manufacturers and service providers both reported lower levels of output in July. The downturn was more severe in manufacturing, where production contracted at the fastest pace since May 2009. Service sector business activity fell for the sixth month running, though the rate of decline eased to its weakest since March.

The worst performers by far were Italy and Spain. The rate of contraction in France slowed marginally, while the downturn in Germany was the steepest for over three years.

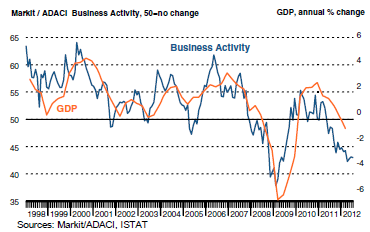

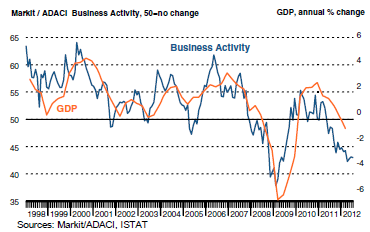

Comment:Markit/ADACI Italy Services PMI®

Chris Williamson, Chief Economist at Markit said:

“The final PMI data for July confirm the message from the earlier flash estimate that the Eurozone continued to contract at a quarterly rate of approximately 0.6% in July, suggesting the region looks set for a second consecutive quarterly decline.

“With incoming new business falling at the fastest rate for three years and service sector companies becoming the gloomiest about the outlook since early-2009, there seems little prospect of any improvement soon.

Markit reports Italy Service Sector New Work Drops at Fastest Rate Since March 2009

Key points:

- Activity falls markedly as a result of accelerated decline in new business

- 12-month outlook turns negative for first time in series history

- Rate of job shedding fastest for three months

Summary:

Conditions across Italy’s service sector took a turn for the worse in July, as incoming new business fell at the fastest rate since March 2009. Activity and

employment both dropped as a result, and for the first time since the launch of the survey in January 1998 firms generally expected output to be lower in a year’s time than current levels. Another negative development for businesses was a slight rise input price inflation from June’s seven-month low.

Outstanding business at services firms was further reduced during the latest survey period, extending the current sequence of decline to 17 months. Moreover, the overall rate of depletion quickened to the fastest since September 2009. Weakness in new business inflows was the most frequently cited reason for lower backlogs.

Read more at http://globaleconomicanalysis.blogspot.com/2012/08/eurozone-new-business-sinks-at-fastest.html#PEdSbIDbutkPwB1V.99

Comment:Markit France Services PMI®

Phil Smith, economist at Markit and author of the Italy Services PMI® said:

"July PMI data pointed to recession in Italy’s service sector deepening at the start of the third quarter. New business intakes fell at a sharp monthly rate that has been exceeded only four times over the series history, all of which occurred around the

height of the global financial crisis. Furthermore, data on expectations showed sentiment at a record low, and gave no impression of an impending recovery."

“Not only did July see a further deterioration on the demand front, but input cost inflation also picked up from June’s recent low. This placed greater pressure on service providers to reduce their overheads, with a solid and accelerated decrease in employment levels one outcome. At the same time, backlogs of work were still reduced at a marked pace, suggesting yet more scope for job cuts.”

Markit reports Stabilisation of French service sector activity during July

Key points:

- Final Markit France Services Activity Index(1) at 50.0 (47.9 in June), 4-month high.

- Final Markit France Composite Output Index(2) at 47.9 (47.3 in June), 4-month high.

Summary:

French service providers reported that business activity was unchanged during July. That followed declines in each of the previous three months. New business and backlogs of work both fell at slower rates, but companies nevertheless made sharper cuts to staffing levels. Competitive pressures led to a further drop in output charges, despite another rise in input costs. Panel members signalled a weaker outlook with regards to future activity, with optimism falling to the lowest level for almost three-and-a-half years.

Manufacturers reported a steeper fall in output during July, with the rate of decline accelerating to the fastest since April 2009. Overall private sector activity was down for the fifth successive month, although the latest drop was the slowest since March.

The level of new business placed with French service providers fell for the fourth month running during July.

Manufacturers reported a further marked decrease in new orders during July, with the rate of contraction accelerating since the previous month. However, overall new business across the private sector fell at the slowest rate since March.

The rate of decline in service sector outstanding business also eased in July. The latest fall in unfinished work was the seventh in successive months, although the weakest since March.

Employment showed a deteriorating trend, with the pace of contraction accelerating to the sharpest since March 2010. Job losses were attributed by panellists to cost-saving strategies, often including decisions not to replace voluntary leavers.

With manufacturers also recording a steeper drop in staffing levels, overall employment across the French private sector fell at the fastest rate since January 2010.

Markit Germany Services PMI®

Markit reports Services activity rises slightly, despite sharpest drop in new work since June 2009

Key points:

- Final Germany Services Business Activity Index(1) at 50.3 in July, up from 49.9 in June.

- Final Germany Composite Output Index(2) at 47.5 in July, down from 48.1 in June.

Summary:

At 50.3 in July, up slightly from 49.9 in June, the final seasonally adjusted Markit Germany Services Business Activity Index posted back above the neutral 50.0 threshold. However, the latest reading signalled only a fractional expansion of overall business activity, and was well below the long-run survey average (53.0). July data indicated that growth was largely driven by Hotels & Restaurants and Renting & Business Activities.

July data highlighted by a marked reduction in new business intakes in the service sector. Lower volumes of new work have now been recorded for four consecutive months and the rate of contraction reached its fastest since June 2009. Five of the six broad areas of the service economy recorded a drop in new business during the latest survey period, with Hotels & Restaurants the exception.Markit Spain Services PMI®

Meanwhile, overall new business intakes across the German private sector also declined at the fastest rate since June 2009.

Markit reports New orders decrease at fastest pace since October 2011

Key points:Activity has now fallen in 13 successive months, and the latest reduction was only marginally slower than seen in June. Hotels & Restaurants was the only sector to record activity growth, while the fastest reduction was recorded at Post & Telecommunications companies.

Further sharp falls in activity and new orders

Sentiment lowest in 38 months

Rate of job cuts accelerates

Summary:

The Spanish service sector continued to struggle at the start of the second half of 2012 as the ongoing economic crisis in Spain impacted negatively on business conditions. Activity, new orders and employment all decreased again over the month, with the fall in new business the sharpest since last October. Furthermore, companies forecast a decline in activity over the next 12 months as sentiment dropped to the lowest in more than three years.

Respondents indicated that falling new business had been the main factor behind the drop in activity. In turn, new orders declined as clients were hesitant to embark on new projects given deteriorating economic conditions. New orders fell at a sharp pace that was the fastest since October 2011.

Companies worked through outstanding business in July as new orders decreased. Backlogs of work were depleted at a substantial pace, and the steepest in seven months.

Service providers continued to lower their staffing levels during July. Employment has now fallen in each of the past 53 months. The rate of job shedding was substantial, and faster than that recorded in June. Of the six monitored sectors, the sharpest fall in employment was posted at Renting & Business Activities companies.

Services companies expect activity to fall over the coming 12 months, the first time this has been the case since May 2009. The forthcoming rise in VAT is forecast to further reduce consumer demand, and therefore business activity.

Comment:Eurozone New Orders

Commenting on the Spanish Services PMI® survey data, Andrew Harker, economist at Markit and author of the report said:

"Perhaps the most worrying aspect of the latest survey is the lowest business sentiment in more than three years, partly reflecting the negative expected impact on consumption of the forthcoming rise in VAT."

Eurozone GDP is going to decline rapidly and businesses will shed workers if new orders continue to decline. Let's look at the new orders, expectations, and employment components from the above reports.

- Eurozone Composite: Incoming new business falling at the fastest rate for three years

- Italy: Activity falls markedly as a result of accelerated decline in new business

- Italy: 12-month outlook turns negative for first time in series history

- Italy: Rate of job shedding fastest for three months

- France: New business and backlogs of work both fell at slower rates, but companies nevertheless made sharper cuts to staffing levels.

- France: The level of new business placed with French service providers fell for the fourth month running during July.

- France: Overall employment across the French private sector fell at the fastest rate since January 2010.

- Germany: Lower volumes of service sector new work have now been recorded for four consecutive months and the rate of contraction reached its fastest since June 2009.

- Germany: Five of the six broad areas of the service economy recorded a drop in new business during the latest survey period, with Hotels & Restaurants the exception.

- Germany: New business intakes across the entire German private sector declined at the fastest rate since June 2009.

- Spain: Activity, new orders and employment all decreased again over the month, with the fall in new business the sharpest since last October.

- Spain: Companies forecast a decline in activity over the next 12 months as sentiment dropped to the lowest in more than three years.

- Spain: Employment has now fallen in each of the past 53 months. The rate of job shedding was substantial, and faster than that recorded in June.

- Spain: Lowest business sentiment in more than three years

- Spain: The forthcoming rise in VAT is forecast to further reduce consumer demand, and therefore business activity.

Countries struggling to meet budget targets have responded by raising taxes. The result of that stupidity can easily be predicted in advance: economic activity will contract further, causing budget target shortfalls.

Yet, Spain is hiking taxes to appease the bureaucrats in Brussels.

In France, prime minister Francois Hollande is about to Wreck France With Economically Insane Proposal: "Make Layoffs So Expensive For Companies That It's Not Worth It"

I wrote that before socialists took over both houses in French parliament. Many suggested he would not follow through. Unfortunately he has. Please consider my July 16 post Peugeot Has 51% Chance of Debt Default; Hollande Says France Will Not Let Peugeot Lay Off Workers

Hollande is also raising taxes like mad and French businesses are likely to head to the UK and other places in response. Many wealthy have fled the country.

Correct Approach

The correct approach is to reduce taxes and make it easier for businesses to fire workers. Logic dictates that if it's difficult or impossible to fire workers, businesses will not hire them in the first place.

Ass-Backwards Eurozone Policies

Most countries in Europe now have ass-backwards policies in place. The silver lining in this mess is those ass-backwards policies will accelerate the breakup of the eurozone, and that is a good thing.

and.....

http://www.prudentbear.com/index.php/creditbubblebulletinview?art_id=10692

Think Grand Canyon

- August 03, 2012

Things get wackier by the week. My proposition has been that once a Credit crisis comes to afflict the “core” (gravitating from the “periphery”) the deleterious consequences tend to be irreversible. As such, with Spain now engulfed in full-fledged financial, economic, political and social crisis, the overall European debt crisis has turned interminable. Of course, desperate politicians and central bankers promise to do whatever it takes to finally resolve the crisis. “Pointless to short the euro,” Mr. Draghi warned yesterday. Their determination is surely intensified by the fact that they are fighting for the very survival of euro monetary integration.

Policymakers and market participants alike appreciate what’s at stake. With global risk markets these days enveloped in an extraordinary “risk on, risk off” speculative melee, the historic battle to “save” the euro has come to dictate global trading dynamics. The European crisis is taking an increasing toll on the global economy, though the incredible measures to combat the bursting of the European Credit Bubble fuel an escalating speculative Bubble throughout global risk markets.

Why does “core” affliction prove such a momentous crisis development? Importantly, the associated costs become enormous and, by definition, the number of parties with the wherewithal to finance a core country bailout turns quite limited. While large, initial Greek bailouts costs were manageable when spread across euro zone partners and a robust ECB. The ultimate costs of bailing out Spain’s banks, regional governments and the sovereign will be many hundreds of billions. And with “robust” a thing of the past, there are scant few places to spread huge prospective bailout expenses. Italy is on the ropes and France is increasingly vulnerable. It is today essentially left to the Germans and the ECB to shoulder the burden of bailout responsibility. And only a small and increasingly isolated minority has an issue with gambling German Creditworthiness and ECB credibility.

It’s been my thesis that there would come a time when the Germans would begin to reevaluate. There are the age old economic issues around “solvency vs. illiquidity” to contend with – along with that fateful “throwing good money after bad” predicament. There is the issue of sacrificing one’s Creditworthiness for the profligacy and misdeeds of others. These issues can be downplayed or completely disregarded - they’re just not going away. At the end of the day, I don’t expect the German people will be willing to shoulder the financial burdens of Spain and Italy. The Germans won’t bury themselves and won’t be blackmailed. And I don’t expect the Bundesbank to completely turn over the keys to the European Central Bank printing press and vault to the MIT trained Italian economist Mario Draghi. There are very deep philosophical differences. Think Grand Canyon.

The markets’ Thursday-to-Friday depressive-manic response to Mr. Draghi was something to behold (being kind here). Reasons behind the about face were not immediately obvious. The Financial Times’ sanguine view didn’t hurt: “Far from moderating his forceful London remarks, Mr Draghi made clear that the ECB is ready to act to stop the disintegration of eurozone financial markets. In a significant step for the ECB’s interpretation of its own role, he left no doubt that the central bank considers it ‘squarely’ within its mandate to counteract ‘convertibility risk’ – the market effect produced by doubts that the euro will survive intact. Mr Draghi, in combative mood, declared that the euro is here to stay: it is ‘pointless’ to bet against it – a big statement.”

The FT editorial made its own big statement: “Investors… should not underestimate the adroitness of Mr. Draghi’s political manoeuvre.” Candidly, I missed it when watching Mr. Draghi’s press conference; few were thinking impressively adroit on Thursday. After the previous week’s bluster, Mr. Draghi simply didn’t have the goods. Moreover, he seemed content to dig a deeper hole for himself. Indeed, one was left assuming that his latest big bazooka idea wasn’t about to pass muster with an increasingly alarmed Bundesbank. But that was Thursday thinking.

Capturing the much-improved Friday market mood – and the markets’ imagination – was a big statement from an ECB policymaker: “There are 23 members in the council and if there will be a vote then everyone’s vote has the same weight in the sense that some questions are solved by a majority.” Rather bold for a new member of the ECB’s rate setting committee from the Bank of Estonia to claim his bank’s vote is as powerful as that from the esteemed Bundesbank.

Especially by week’s end, markets were happy to disregard what I believe were telling comments from prominent Bundesbank officials – current and former. Mr. Otmar Issing penned a brilliant op-ed for Monday’s Financial Times, “Europe’s Political Union is Worthy of Satire.” This was followed by “the Bundesbank celebrates its 55th birthday on 1 August and continues to stand for an exceptionally strong orientation to stability,” with the Bundesbank’s website highlighting an insightful interview with current Bundesbank President Jens Weidmann and former (1991-1993) head Helmut Schlesinger. Considering the backdrop, I thought this interview was worthy of major excerpts.

Mr. Weidmann: “...Despite all our various qualifications and tasks, within the Bank, there is a shared vision and a clear commitment to monetary stability. This is unique for such an institution and has also made the Bank an attractive option for people applying to work for us. The public good of maintaining price stability and thus contributing to the common good is a major incentive for many.”

Mr Weidmann, how did you yourself see the Bundesbank, say, while you were at university?

Mr. Weidmann: “In 1987 I was studying in France. The Banque de France was not yet independent at the time. That is when I first clearly saw the differences in outlook concerning the role of, and oversight over, the central bank. I myself had pretty much ‘inhaled’ the Bundesbank’s role; my French student friends, however, could not possibly imagine a government institution performing a key sovereign task and still being outside parliamentary control. Two very different world views were colliding. They have continued to do so in all political debates – essentially, up to the present day.”

Where can you identify this?

Mr. Weidmann: “I recently gave an interview to the French daily newspaper ‘Le Monde’. Many readers responded to the substantive positioning, some positively, some negatively. However, some responded along the lines of ‘Why is he meddling in the political debate? He’s only a central bank governor, a ‘civil servant’ who actually shouldn’t be saying anything on the matter.”

In 1990, the Bundesbank wrote that the participants in economic and monetary union would be inextricably linked to one another ‘come what may’ and that such a union would be an ‘irrevocable joint and several community which, in the light of past experience, requires a more far-reaching association, in the form of a comprehensive political union, if it is to remain durable’.

Mr. Weidmann: “The assessment at that time merely reflected the Bank’s long-held position. As early as 1963, President Karl Blessing had stated that the introduction of monetary union should be conditional on political union. The Bank’s stance has not only been consistent over time but has, in fact, taken on even greater relevance in a dramatic way owing to the recent crisis in the euro area.”

Political union did not feature in the Maastricht Treaty at the end of 1991. How did the Central Bank Council react to this?

Mr. Schlesinger: “When I took office as President of the Deutsche Bundesbank in the summer of 1991, Chancellor Helmut Kohl was still in favour of political union. However, the decision to implement monetary union by no later than 1999 was taken just four months later. This was a clear defeat for us. There is no other way of putting it. We had assumed that the Treaty would be concluded with a definition of the entry criteria, but without a fixed date being set.”

Mr. Weidmann: “It is interesting that we are having a similar discussion now in connection with the banking union. Here, too, some quarters are evidently seeking a far-reaching joint solution, but without imposing stricter rules on the other policy areas that are also affected. A genuine European banking supervision can indeed form a major component of closer integration within monetary union. However, such an institutional reorganisation of banking supervision also has to be integrated – into a comprehensive reform of the supervisory regulatory framework and of the respective national scope for economic and fiscal policy. Otherwise, too great a burden will be placed on banking supervision.”

What is crucial for political union is the willingness to hand over national sovereignty. Does such a willingness actually exist within the EU?

Mr. Schlesinger: “This question always takes me back to the start of European unification. At that time, the main objective was quite a different one – namely, to ensure that there would never again be a war in Europe. The plan for a common European army was ultimately blocked by France, even though the loss of sovereignty involved would have been easy to implement. It is actually hard to envisage how a loss of monetary sovereignty could be achieved in the absence of a unified state.”

Mr. Weidmann: “Seeing how reluctant some countries are to relinquish their fiscal policy autonomy – even in return for financial assistance – it is hard to imagine political union being achieved in the foreseeable future.”

Mr Schlesinger, should the Bundesbank have fought more strongly against monetary union without a political counterweight in the 1990s?

Mr. Schlesinger: “All of our demands were fulfilled. But I think we all underestimated just how wide the gulf is in the mindset not only of the political class but also in terms of public opinion in the individual countries concerning the objectives of fiscal policy. I would like to refer you to a chapter by Rudolf Richter in the publication marking the 50th anniversary of the Deutsche Mark… He writes that the culture of stability in Germany has been able to develop only because it has had the full backing of the general public. If you look at the Maastricht Treaty, the relevant criteria are there. But you won’t find any reference to the member states having to have the same culture of stability.

Mr. Weidmann: “Political efforts to use the central bank for policy purposes exist in all countries. However, the public’s stance on this is probably the crucial factor.”

Is there a lack of political will?

Mr. Weidmann: “The founding fathers of the EU treaties evidently took a skeptical view of the political will, and it is precisely for this reason that they made the central bank independent in order to protect it from a lack of or a conflict of political will. But the central bank must use and maintain this protection. Furthermore, it should be aware that this independence also requires it to respect and not overstep its own mandate. Mr. Schlesinger’s examples show that what is politically desirable and what is economically prudent have often not matched up. Whether we're talking about interest rates or some sort of non-standard measures, in the end it always comes down to the central bank being instrumentalised for fiscal policy objectives. However, policymakers thereby overestimate the central bank's possibilities and expect too much of it by assuming that it can be used not only for price stability, but also for promoting growth, reducing unemployment and stabilising the banking system. This pattern occurs again and again; this time it is perhaps even more pronounced than in the past because there is increased doubt among the general public about policymakers’ ability to act, and the central bank is seen as the sole institution that is capable of doing something. In this respect, the central bank is perhaps under even more pressure than in the past – even though you, Mr. Schlesinger, are better able to judge this as you have witnessed all of these periods. Furthermore, in Europe we are faced with some quite different ways of looking at the central bank’s role – not only in politics, but also in the media and on the part of the general public. If a central bank also has to work against public opinion, things get difficult.”

Today it is even harder for the Bundesbank to assert its influence as it is just one of 17 central banks in the Eurosystem. What impact does this have on your work?

Mr. Weidmann: “Even though what you say is correct in terms of shares of voting rights, I certainly would not say that we are ‘just’ one of 17 central banks. We are the largest and most important central bank in the Eurosystem and we have a greater say than many other central banks in the Eurosystem. This means that we have a different role. We are the central bank that is most active in the public debate on the future of monetary union. This is also how some of my colleagues expect it to be.”

It is often said that Germany has benefitted from monetary union and it therefore has a duty to help.

Mr. Weidmann: “I think that argument is incorrect. First, counting up the for and against of who has benefited to what extent from monetary union is not helpful. A stable single currency benefits all member states – some perhaps more than others, but that, too, can change over time. After all, Germany was certainly not considered to be a winner during the first few years of monetary union. Second, when monetary union was established, we agreed on a legal framework which has to be respected: a single monetary policy ensures price stability and each member state is responsible for its own fiscal policy. This is precisely what is expressed in the ‘no bail-out’ clause. And third: Germany is already providing large-scale assistance for the peripheral countries, not least as an anchor of stability and as a guarantor of the rescue packages.”

Mr Weidmann, in your opinion, what are the biggest challenges that the Bundesbank is facing now and in the coming years?

Mr. Weidmann: “The crisis requires all our energies. We shall continue to use all of our resources at all levels to stand up for the positions we believe in and to ensure that the monetary union remains a stability union...”

Especially these days, I have little company when it comes to extolling the virtues of the Bundesbank or German economic thinking more generally. For me, it’s an issue of principle. Over the past 22 years I have come to deeply respect the German (including “Austrian”) view of economics, money and Credit, and monetary management. I’m partial to a sound analytical framework, discipline and the so-called “orientation of stability.” Back in 2004, in a CBB titled “Issing vs. Greenspan,” I highlighted a WSJ op-ed by then ECB Chief Economist Otmar Issing, with his prescient warning against central banks ignoring Bubbles:

From Issing’s article, aptly titled “Money and Credit”: “Huge swings in asset valuations can imply significant misallocations of resources in the economy and furthermore create problems for monetary policy. Not every strong decline in asset prices causes deflation, but all major deflations in the world were related to a sudden, continuing and substantial fall in values of assets. The consequences for banks, companies and households can be tremendous… Prevention is the best way to minimize costs for society from a longer-term perspective. …it should not be overlooked that most exceptional increases in prices for stocks and real estate in history were accompanied by strong expansions of money and/or credit.”

This has been a multi-year battle for what constitutes sound analysis and economic doctrine. Mr. Issing and the Bundesbank know they have won the debate on Bubbles, money, Credit and monetary policymaking. There is reason to believe they view U.S. monetary and fiscal policymaking as an ongoing disaster. And it is ironic that markets today celebrate Mr. Draghi’s desperate move to adopt Fed-like quantitative easing. As Mr. Issing wrote this week in the FT, “Juvenal would have said: Difficile est satiram non scribere (It is difficult not to write a satire).”

I suspect the Bundesbank has commenced preparation for a difficult confrontation. I am less clear on the stance of what appears an increasingly divided Merkel government, although a decisive shift in German public sentiment has seemingly begun. According to recent polling (YouGov), only 33% of respondents now support Ms. Merkel’s handling of the euro zone crisis, down sharply over recent weeks. And, for the first time, a majority (51%) of Germans now believe they would be better off without the euro (Merkel was said to be “profoundly disturbed”). The vast majority of Germans want Greece out of the euro, and fewer each week would be content subsidizing profligate Spain and Italy. If either the Bundesbank or the Federal Constitutional Court of Germany should in coming weeks draw a harder line, they might just enjoy an outpouring of support from the German people – if not global risk markets.

and........

http://theeconomiccollapseblog.com/archives/spain-and-italy-are-toast-unless-germany-allows-the-ecb-to-print-trillions-of-euros

The financial chess game in Europe is still being played out, but in the end it is going to boil down to one very fundamental decision. Is Germany going to allow the ECB to print up trillions of euros and use those euros to buy up the sovereign debt of troubled eurozone members such as Spain and Italy or not? Nothing short of this is going to solve the problems in Europe. You can forget the ESM and the EFSF. Anyone that thinks they are going to solve the problems in Europe is someone that would also take a water pistol to fight a raging wildfire. No, the only thing that is going to keep Spain and Italy from collapsing under the weight of a mountain of debt is a financial nuke. The ECB needs to have the power to print up trillions of euros and use that money to buy up massive amounts of sovereign debt in order to guarantee that Spain and Italy will be able to borrow lots more money at very low interest rates. In fact, this is probably what European Central Bank President Mario Draghi has in mind when he says that he is going to "do whatever it takes to preserve the euro". However, there is one giant problem. The ECB is not going to be able to do this unless Germany allows them to. And after enduring the horror of hyperinflation under the Weimar Republic, Germany is not too keen on introducing trillions upon trillions of new euros into the European economy. If Germany allows the ECB to go down this path, Germany will end up experiencing tremendous inflation and the only benefit for Germany will be that the eurozone was kept together. That doesn't sound like a very good deal for Germany.

Right now, the yield on 10 year Spanish bonds is above 7 percent and the yield on 10 year Italian bonds is above 6 percent.

Those are unsustainable levels.

The only thing that is going to bring those bond yields down permanently to where they need to be is unlimited ECB intervention.

But that is not going to happen without German permission.

Meanwhile, the situation in Spain gets worse by the day.

An article in Der Spiegel recently described the slow motion bank run that is systematically ripping the Spanish banking system to shreds....

Capital outflows from Spain more than quadrupled in May to €41.3 billion ($50.7 billion) compared with May 2011, according to figures released on Tuesday by the Spanish central bank.In the first five months of 2012, a total of €163 billion left the country, the figures indicate. During the same period a year earlier, Spain recorded a net inflow of €14.6 billion.

If those numbers sound really bad to you, that is because they are really bad.

At this point, authorities in Spain are starting to panic. According to Graham Summers, Spain has imposed the following new capital restrictions during the last month alone....

- A minimum fine of €10,000 for taxpayers who do not report their foreign accounts.

- Secondary fines of €5,000 for each additional account

- No cash transactions greater than €2,500

- Cash transaction restrictions apply to individuals and businesses

How would you feel if the U.S. government permanently banned all cash transactions greater than $2,500?

That is how crazy things have already become in Spain.

We should see the government of Spain formally ask for a bailout pretty soon here.

Italy should follow fairly quickly thereafter.

But right now there is not enough money to completely bail either one of them out.

In the end, either the ECB is going to do it or it is not going to get done.

A moment of truth is rapidly approaching for Europe, and nobody is quite sure what is going to happen next. According to the Wall Street Journal, the central banks of the world are on "red alert" at this point....

Ben Bernanke and Mario Draghi, with words but not yet actions, demonstrated this week that they are on red alert about the global economy.Expectations are now high that Mr. Bernanke's Federal Reserve and Mr. Draghi's European Central Bank will act soon to address those worries. But both face immense tactical and political challenges and neither has a handbook to follow.

So what happens if Germany does not allow the ECB to print up trillions of new euros?

Financial journalist Ambrose Evans-Pritchard recently described what is at stake in all of this....

Failure to halt a full-blown debt debacle in Spain and Italy at this delicate juncture - with China, India and Brazil by now in the grip of a broken credit cycle and the US on the cusp of fresh recession even before the “fiscal cliff” hits - would tip the entire global system into a downward spin, triggering the sort of feedback loop that caused such havoc in late 2008.

As I have written about so frequently, time is running out for the global financial system.

Even Germany is starting to feel the pain. This week we learned that unemployment in Germany has risen for four months in a row.

So what comes next?

There is actually a key date that is coming up in September. The Federal Constitutional Court in Germany will rule on the legality of German participation in the European Stability Mechanism on September 12th.

If it is ruled that Germany cannot participate in the European Stability Mechanism then that is going to create all sorts of chaos. At that point all future European bailouts would be called into question and many would start counting down the days to the break up of the entire eurozone.

If Germany did end up leaving the eurozone, the transition would not be as difficult as many may think.

For example, most Americans may not realize this but Deutsche Marks are currently accepted at many retail stores throughout Germany. The following comes from a recent Wall Street Journal article....

Shopping for pain reliever here on a recent sunny morning, Ulrike Berger giddily counted her coins and approached the pharmacy counter. She had just enough to make the purchase: 31.09 deutsche marks."They just feel nice to hold again," the 55-year-old preschool teacher marveled, cupping the grubby coins fished from the crevices of her castaway living room sofa. "And they're still worth something."Behind the counter of Rolf-Dieter Schaetzle's pharmacy in this southern German village lay a tray full of deutsche mark notes and coins—a month's worth of sales.

I have a feeling that it would be much easier for Germany to leave the euro than it would be for most other eurozone members to.

The months ahead are certainly going to be very interesting, that is for sure.

Europe is heading for a date with destiny, and what transpires in Europe is going to shake the rest of the globe.

Sadly, most Americans still aren't too concerned with what is going on in Europe right now.

Well, if you still don't think that the problems in Europe are going to affect the United States, just check this news item from the Guardian....

General Motors' profits fell 41% in the second quarter as troubles in Europe undercut strong sales in North America.America's largest automaker made $1.5bn in the second quarter of 2012, compared with $2.5bn for the same period last year. Revenue fell to $37.6bn from $39.4bn in the second quarter of 2011. The results exceeded analysts' estimates, but further underlined Europe's drag on the US economy.

Profits at General Motors are down 41 percent and Europe is being blamed.

The global economy is more tightly integrated than ever before, and there is no way that the financial system of Europe collapses without it taking down the United States as well.

And considering the fact that the U.S. economy has already been steadily collapsing, the last thing we need is for Europe to come along and take our legs out from underneath us.

So what do all of you think about the problems in Europe?

Do you see any possible solution?

No comments:

Post a Comment