Business Insider.....

More critical weaknesses have been uncovered in the OpenSSL web encryption standard, just two months after the disclosure of the notorious Heartbleed vulnerability affecting the same technology.

More critical weaknesses have been uncovered in the OpenSSL web encryption standard, just two months after the disclosure of the notorious Heartbleed vulnerability affecting the same technology.

Krebs on Security.....

There Is A New OpenSSL Bug That May Be More Dangerous Than Heartbleed

Lisa Eadicicco

Tatsuya Hayashi, the researcher who found one of the critical bugs, told the Guardian that the latest flaw "may be more dangerous than Heartbleed" as it could be used to directly spy on people's communications.

Heartbleed was deemed to be one of the most critical internet vulnerabilities ever when it was uncovered in April. OpenSSL is supposed to protect people’s data with digital keys but has been exposed as flawed numerous times in recent months.

The latest vulnerability was introduced in 1998 and has been missed by both paid and volunteer developers working on the open-source project for 16 years.

Meanwhile, one of the other severe vulnerabilities in OpenSSL detailed this week was introduced by the same man responsible for the Heartbleed flaw, researchers said.

Using the vulnerability found by Hayashi, attackers sitting on the same network as a target, such as on the same public Wi-Fi network, could force weak encryption keys on connections between victims’ PCs and web servers.

With knowledge of those keys, the attacker could intercept data. They could even change the data being sent between the user and the website to trick the victim into handing over more sensitive information, such as usernames and passwords. This is known as a "man-in-the-middle" attack.

“Under the public Wi-Fi network situations, attackers can very easily eavesdrop and make falsifications on encrypted communications,” Hayashi added. “Victims cannot detect any trace of the attacks.”

The vulnerability affects all PC and mobile software using OpenSSL prior to the latest version, believed to include the Chrome browser on Android phones, and servers running OpenSSL 1.0.1 and the beta version for 1.0.2.

Many website owners will be running OpenSSL 1.0.1 as it fixed the Heartbleed vulnerability. Fixes have been issued by the team managing OpenSSL, which encrypts people’s internet traffic going to and from millions of web services around the world.

Internet users running vulnerable versions have been urged to install the patches, as detailed on the OpenSSL advisory, which included fixes for range of other flaws.

One of those other vulnerabilities, which could have allowed an attacker to send malicious code to affected machines running OpenSSL and therefore have them leak data, was introduced by the same developer as Heartbleed, Robin Seggelmann, four years ago, according to an HP blog post.

The job of fixing the bug found by Hayashi is likely to be far bigger than Heartbleed, warned Nick Percoco, vice president of strategic services from security firm Rapid7.

“From a remediation standpoint it is actually worse for organisations running OpenSSL on the server side. Heartbleed only affected versions back about two years," he said.

"This issue goes back to the first release of OpenSSL in 1998. That means there were likely many people running version that were not affected by Heartbleed that didn’t patch last time."

Many popular browsers appear to be safe from attack, however, noted Google security engineer Adam Langley, in another blog post. “Non-OpenSSL clients (Internet Explorer, Firefox, Chrome on Desktop and iOS, Safari, etc) aren't affected. None the less, all OpenSSL users should be updating,” he said.

Prof Alan Woodward, security expert from the department of computing at the University of Surrey, said he wasn’t sure the bug was as bad as Heartbleed due to its constraints - for example, both the server and the client must be vulnerable at the time of the attack. But the flaw has been left open for so long and affects so many servers that it showed OpenSSL was heading towards its death as a reliable form of protection, he said.

“It’s been there all along since OpenSSL first launched and no one has found it before, which tells you something about how thoroughly these open-source tools are checked,” Woodward told the Guardian.

“It does seem like another nail in the coffin for OpenSSL. It may not be dead but this must be another blow to people’s confidence.”

Krebs on Security.....

05

JUN 14

JUN 14

They Hack Because They Can

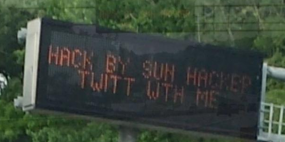

The Internet of Things is coming….to a highway sign near you? In the latest reminder that much of our nation’s “critical infrastructure” is held together with the Internet equivalent of spit and glue, authorities in several U.S. states are reporting that a hacker has once again broken into and defaced electronic road signs over highways in several U.S. states.

Earlier this week, news media in North Carolina reported that at least three highway signs there had apparently been compromised and re-worded to read “Hack by Sun Hacker.” Similar incidents were reported between May 27 and June 2, 2014 in two other states, which spotted variations on that message left by the perpetrator, (including an invitation to chat with him on Twitter).

The attack was reminiscent of a series of incidents beginning two years ago in which various electronic message signs were changed to read “Warning, Zombies Ahead”.

While at least those attacks were chuckle-worthy, messing with traffic signs is no laughing matter: As a report by the Multi-State Information Sharing and Analysis Center (MS-ISAC) points out, changes to road signs create a public safety issue because instead of directing drivers through road hazards, they often result in drivers slowing or stopping to view the signs or take pictures.

That same MS-ISAC notice, obtained by KrebsOnSecurity and published here (PDF), points out that these incidents appear to be encouraged by sloppy security on the part of those responsible for maintaining these signs.

“Investigators in one state believe the compromise may be in part due to the use of weak Simple Network Management Protocol (SNMP) community strings. Investigators in another state believe the malicious actor used Telnet port 23 and a simple password cracker to gain remote access. In one state the malicious actor changed the modem passwords, forcing technicians to restore to factory default settings to regain access.”

02

JUN 14

JUN 14

‘Operation Tovar’ Targets ‘Gameover’ ZeuS Botnet, CryptoLocker Scourge

The U.S. Justice Department is expected to announce today an international law enforcement operation to seize control over the Gameover ZeuS botnet, a sprawling network of hacked Microsoft Windows computers that currently infects an estimated 500,000 to 1 million compromised systems globally. Experts say PCs infected with Gameover are being harvested for sensitive financial and personal data, and rented out to an elite cadre of hackers for use in online extortion attacks, spam and other illicit moneymaking schemes.

This graphic, from 2012, shows the decentralized nature of P2P network connectivity of 23,196 PCs infected with Gameover. Image: Dell SecureWorks

The sneak attack on Gameover, dubbed “Operation Tovar,” began late last week and is a collaborative effort by investigators at the FBI, Europol, and the UK’s National Crime Agency; security firmsCrowdStrike, Dell SecureWorks,Symantec, Trend Micro and McAfee; and academic researchers at VU University Amsterdam and Saarland University in Germany. News of the action first came to light in a blog post published briefly on Friday by McAfee, but that post was removed a few hours after it went online.

Gameover is based on code from the ZeuS Trojan, an infamous family of malware that has been used in countless online banking heists. Unlike ZeuS — which was sold as a botnet creation kit to anyone who had a few thousand dollars in virtual currency to spend — Gameover ZeuS has since October 2011 been controlled and maintained by a core group of hackers from Russia and Ukraine.

Those individuals are believed to have used the botnet in high-dollar corporate account takeovers that frequently were punctuated by massive distributed-denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks intended to distract victims from immediately noticing the thefts. According to the Justice Department, Gameover has been implicated in the theft of more than $100 million in account takeovers.

The curators of Gameover also have reportedly loaned out sections of their botnet to vetted third-parties who have used them for a variety of purposes. One of the most popular uses of Gameover has been as a platform for seeding infected systems with CryptoLocker, a nasty strain of malware that locks your most precious files with strong encryption until you pay a ransom demand.

According to a 2012 research paper published by Dell SecureWorks, the Gameover Trojan is principally spread via Cutwail, one of the world’s largest and most notorious spam botnets (for more on Cutwail and its origins and authors, see this post). These junk emails typically spoof trusted brands, including shipping and phone companies, online retailers, social networking sites and financial institutions. The email lures bearing Gameover often come in the form of an invoice, an order confirmation, or a warning about an unpaid bill (usually with a large balance due to increase the likelihood that a victim will click the link). The links in the email have been replaced with those of compromised sites that will silently probe the visitor’s browser for outdated plugins that can be leveraged to install malware.

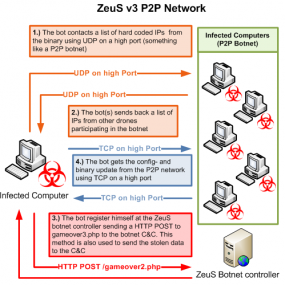

It will be interesting to hear how the authorities and security researchers involved in this effort managed to gain control over the Gameover botnet, which uses an advanced peer-to-peer (P2P) mechanism to control and update the bot-infected systems.

The addition of the P2P component in Gameover is innovation designed to make it much more difficult for security experts, law enforcement or other Internet do-gooders to dismantle the botnet. In March 2012,Microsoft used a combination of legal maneuvering and surprise to take down dozens of botnets powered by ZeuS (and its code-cousin — SpyEye), by seizing control over the domain names that the bad guys used to control the individual ZeuS botnets.

But Gameover would be far trickier to disrupt or wrest from its creators: It uses a tiered, decentralized system of intermediary proxies and strong encryption to hide the location of servers that the botnet masters use to control the crime machine.

“Microsoft’s 2012 takedown action had no effect on the P2P version of ZeuS because of its network architecture,” reads Dell SecureWorks’s 2012 paper on Gameover. “In the P2P model of ZeuS, each infected client maintains a list of other infected clients. These peers act a massive proxy network between the P2P ZeuS botnet operators and the infected hosts. The peers are used to propagate binary updates, to distribute configuration files, and to send stolen data to the controllers.”

According to McAfee, the seizure of Gameover is expected to coincide with a cleanup effort in which Internet service providers contact affected customers to help remediate compromised PCs. The Department of Homeland Security’s U.S. Computer Emergency Readiness Team (US-CERT) today published a list of resources that may help in that effort.

Update, 11:07 a.m. ET: The Justice Department just published a complaint (PDF) that names the alleged author of the ZeuS Trojan, allegedly a Russian citizen named Evgeniy Mikhailovich Bogachev. The complaint mentions something that this blog has noted on several occasions - that the the ZeuS author used multiple nicknames, including “Slavik” and “Pollingsoon.” More court documents related to today’s action are available here.

Yevgeniy Bogachev, Evgeniy Mikhaylovich Bogachev, a.k.a. “lucky12345″, “slavik”, “Pollingsoon”. Source: FBI.gov “most wanted, cyber.

30

MAY 14

MAY 14

Thieves Planted Malware to Hack ATMs

A recent ATM skimming attack in which thieves used a specialized device to physically insert malicious software into a cash machine may be a harbinger of more sophisticated scams to come.

Two men arrested in Macau for allegedly planting malware on local ATMs (shown with equipment reportedly seized from their hotel room).

Authorities in Macau — a Chinese territory approximately 40 miles west of Hong Kong — this week announced the arrest of two Ukrainian men accused of participating in a skimming ring that stole approximately $100,000 from at least seven ATMs. Local police said the men used a device that was connected to a small laptop, and inserted the device into the card acceptance slot on the ATMs.

Armed with this toolset, the authorities said, the men were able to install malware capable of siphoning the customer’s card data and PINs. The device appears to be a rigid green circuit board that is approximately four or five times the length of an ATM card.

According to local press reports (and supplemented by an interview with an employee at one of the local banks who asked not to be named), the insertion of the circuit board caused the software running on the ATMs to crash, temporarily leaving the cash machine with a black, empty screen. The thieves would then remove the device. Soon after, the machine would restart, and begin recording the card and PINs entered by customers who used the compromised machines.

The Macau government alleges that the accused would return a few days after infecting the ATMs to collect the stolen card numbers and PINs. To do this, the thieves would reinsert the specialized chip card to retrieve the purloined data, and then a separate chip card to destroy evidence of the malware. Here’s a look at the devices that Macau authorities say the accused used to insert the malware into ATMs (I’m working on getting clearer photos of this hardware):

Five of the devices Macau police say the thieves used to insert the malware and retrieve stolen data.

Here is a side-view look at the circuit board device:

And finally, a close-up of one end of the skimming board itself:

ATM attacks that leverage external, physical access to install malware aren’t exactly new, but they’re far less common than skimming devices that are made to be affixed to the cash machine for the duration of the theft. It’s not clear how the malware is being delivered in this case, but in previous attacks of this sort the thieves have been able to connect directly to a USB port somewhere inside the ATMs.

Late last year, a pair of researchers at the Chaos Communication Congress (CCC) conference in Germany detailed a malware attack that drained ATMs at unnamed banks in Europe. In that attack, the crooks cut a chunk out of the ATM’s chassis to expose its USB port, and then inserted a USB stick loaded with malware. The thieves would then replace the cut-out piece of chassis and come back a few days later, and enter a 12-digit code that launched a special interface that displayed the amount of money available in each denomination — along with options for dispensing each kind.

In December 2012, I wrote about an attack in Brazil in which thieves swapped an ATM’s USB-based security camera with a portable keyboard that let them hack the cash machine. In that attack, the crook caused a reboot of the ATM software by punching in a special combination of keys. The thieves then were able to reboot into a custom version of Debian Linux designed to troubleshoot locked or corrupted ATM equipment.

No comments:

Post a Comment