http://my.firedoglake.com/masaccio/2013/01/23/breuer-identifies-real-clients-on-frontline-then-quits/#recommend-78797-165

Lanny Breuer is out as head of the Criminal Division of the Department of Justice, according to the Washington Post. After his ratlike performance on Frontline (transcript here) it won’t be long before we find him at some creepy New York or DC law firm defending his best friends, the banks and their sleazy employees. His legacy is simple: too big to fail banks can’t possibly commit crimes, so minor civil fines and false promises of reform are punishment enough.Jamie Dimon couldn’t have put it better.

http://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2013/01/for-once-maybe-lying-does-not-pay-dojs-lanny-breuer-resigns-abruptly-after-frontline-appearance.html

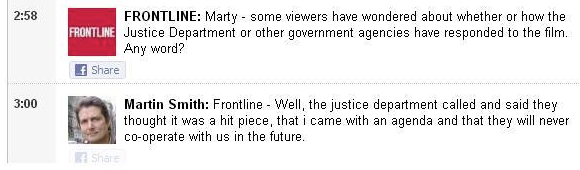

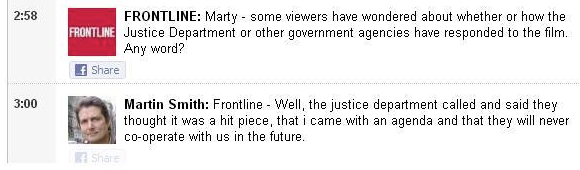

Here are is one howler from his Frontline performance (the bold is the Frontline interviewer):

Read more at http://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2013/01/for-once-maybe-lying-does-not-pay-dojs-lanny-breuer-resigns-abruptly-after-frontline-appearance.html#BwcvGUqEXyvOFJkb.99

http://www.zerohedge.com/news/2013-01-23/assistant-attorney-general-breuer-leave-doj-untouchables-aftermath

Breuer Identifies Real Clients on Frontline then Quits | |

| By: masaccio Wednesday January 23, 2013 4:03 pm | |

Lanny Breuer is out as head of the Criminal Division of the Department of Justice, according to the Washington Post. After his ratlike performance on Frontline (transcript here) it won’t be long before we find him at some creepy New York or DC law firm defending his best friends, the banks and their sleazy employees. His legacy is simple: too big to fail banks can’t possibly commit crimes, so minor civil fines and false promises of reform are punishment enough.Jamie Dimon couldn’t have put it better.

Breuer tried his best to dodge questions about why he violated his promise to Senator Kaufman that he was actually conducting an investigation of Wall Street fraud. Martin Smith, the interviewer, asks:

We spoke to a couple of sources from within the fraud section of the Criminal Division, and through mid-2010 they reported that when it came to Wall Street, there were no investigations going on; there were no subpoenas, no document reviews, no wiretaps.

Breuer responds: “we looked very hard at the types of matters that you’re talking about.” He doesn’t deny that there were no investigations; no subpoenas, no document reviews, no wiretaps. Instead, he tries to shift the subject to his pointless insider trading cases, his Ponzi cases, the Lee Farkas case (the mortgage firm Taylor, Whitaker and Bean), and a few hapless mortgage originator cases, and even a policeman defrauded by some fraud or other. Smith won’t let that pass. Eventually we get to the heart of the problem to Breuer:

But in those cases where we can’t bring a criminal case — and federal criminal cases are hard to bring — I have to prove that you had the specific intent to defraud. I have to prove that the counterparty, the other side of the transaction, relied on your misrepresentation. If we cannot establish that, then we can’t bring a criminal case.But in reality, in a criminal case, we have to prove beyond a reasonable doubt — not a preponderance, not 51 percent — beyond any reasonable doubt that a crime was committed. And I have to prove not only that you made a false statement but that you intended to commit a crime, and also that the other side of the transaction relied on what you were saying. And frankly, in many of the securitizations and the kinds of transactions we’re talking about, in reality you had very sophisticated counterparties on both sides.Smith says “You do have plaintiffs who will come forward and say that they relied on the reps and warranties, and they relied on the due diligence claims that were made by the bank.”Breuer keeps talking, but he can’t worm out of this one. Smith then says:“We’ve spoken to people inside the Residential Mortgage-Backed Securities Working Group who said that when they began their work in January, February, March of 2012 that they found nothing at the Justice Department in the pipeline, no ongoing cases looking at securitization.”And lest we forget, Lanny reminds us that these cases have ramifications for the rest of the bank. I don’t know who told Breuer that indicting the investment banking arm of a megabank would destroy the bank, but that’s a piece of idiocy that he claims to believe. This is from a speech he gave last September:In my conference room, over the years, I have heard sober predictions that a company or bank might fail if we indict, that innocent employees could lose their jobs, that entire industries may be affected, and even that global markets will feel the effects. Sometimes – though, let me stress, not always – these presentations are compelling. In reaching every charging decision, we must take into account the effect of an indictment on innocent employees and shareholders, just as we must take into account the nature of the crimes committed and the pervasiveness of the misconduct. I personally feel that it’s my duty to consider whether individual employees with no responsibility for, or knowledge of, misconduct committed by others in the same company are going to lose their livelihood if we indict the corporation. In large multi-national companies, the jobs of tens of thousands of employees can be at stake. And, in some cases, the health of an industry or the markets are a real factor. Those are the kinds of considerations in white collar crime cases that literally keep me up at night, and which must play a role in responsible enforcement.This concern is so touching. Too bad he and his team of responsible enforcers never thought about the impact on the families of Aaron Swarz, or any of the countless people serving time for possessing pot, or whistleblowers like John Kirakou and Thomas Drake.The persistent questioning exposes Breuer’s idea of a hard look: he and his crack prosecutors read the offering documents and let the lawyers for the crooks explain why they make it just fine. They don’t need to issue subpoenas for e-mails that drive the civil cases filed by retirement funds and hedge funds that got screwed by the megabanks. They don’t need to haul the clerks and the functionaries into Grand Juries and find out what they knew and who they told. They don’t need to work up the chain to their bosses and on to the top. They don’t need to identify the lawyers from those white shoe firms that wrote those weasel words into the documents, haul them into the Grand Jury room and find out exactly what they knew and what those words meant. And most important, there is no need to let a jury decide their guilt. Breuer does all that for us.Breuer is sleazy. But remember, he takes his orders from Attorney General Eric Holder and President Barack Obama. This administration refuses to prosecute.

http://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2013/01/for-once-maybe-lying-does-not-pay-dojs-lanny-breuer-resigns-abruptly-after-frontline-appearance.html

WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 23, 2013

For Once, Maybe Lying Does Not Pay: DoJ’s Lanny Breuer Resignation Leaked After Frontline Appearance

I am delighted to be proven to be wrong on the premise of the last post, which is that lying pays and it has become so routine that an op-ed writer for a liberal newspaper can point that out without being concerned about the broader ramifications. But this is almost certain to fall into “the exception that proves the rule” category.

Lanny Breuer, former Covington & Burling partner and more recently head of the criminal division at the Department of Justice, had his resignation leaked today. The proximate cause may be a Frontline show that ran two nights ago, part of a series on the financial crisis.

Breuer has been criticized for his lack of interest in prosecuting banks and more important, bank executives for their conduct during the crisis (and before you argue that such cases are difficult to make, please read Charles Ferguson’s Predator Nation, which selects specific banks and shows how, simply based on public information, a clear and compelling case exists, or look at some of our posts, for instance, here). He also was the DoJ co-chairman on the do-virtually-nothing residential mortgage task force formed as a way to suborn Eric Schneiderman, who was leading a group of state attorney generals that were on their way to putting in place tougher sanctions in the banks. We’ve noted how it was Breuer who had taken to embarrassing Schneiderman for his choice:

The Administration started undercutting Schneiderman almost immediately. He announced that the task force would have “hundreds” of investigators. Breuer said it would have only 55, a simply pathetic number (the far less costly savings & loan crisis had over 1000 FBI agents assigned to it). And they taunted him publicly by exposing that he hadn’t gotten a tougher release as he has claimed to justify his sabotage….Marcy Wheeler, who has called repeatedly for Breuer’s resignation, was early to catch that Breuer would be departing. It’s not clear whether the proximate cause was just his performance or whether that plus the ham-handed pushback, which created a Twitter storm, was what made his cause irredeemable:

Here are is one howler from his Frontline performance (the bold is the Frontline interviewer):

But it has nothing to do with the financial crisis, the meltdown, the packaging of bad mortgages that led to the collapse that led to the recession.

First of all, I think that the financial crisis is multifaceted. But even within that, all we can do is look hard at this multifaceted, multipronged problem. And what we’ve had is a multipronged, multifaceted response.

When a criminal case can be brought, whether it’s from an originator, whether it’s from a bank executive who acted with criminal intent, we’ve brought those cases.

But in those cases where we can’t bring a criminal case — and federal criminal cases are hard to bring — I have to prove that you had the specific intent to defraud. I have to prove that the counterparty, the other side of the transaction, relied on your misrepresentation. If we cannot establish that, then we can’t bring a criminal case.

But we don’t let these institutions go. We’ve brought civil cases. We’ve brought regulatory cases. And the entire approach here is to have a multipronged, comprehensive approach to what gave rise to the financial crisis.

This is nonsense. We’ve discussed at length how top bank executives could be prosecuted for making false certifications under Sarbanes Oxley, which requires at a minimum that the bank certify the adequacy of internal controls, which for a large trading firm, includes risk management. We’ve also written about collusion and lack of arm’s length pricing in the CDO market, which would lend themselves to antitrust charges (price fixing is criminal under the Sherman Act). This is a Department of Justice that has been willing to pursue creative, more accurately, strained legal theories to go after John Edwards, and used a weak case to destroy Aaron Swartz, but becomes remarkably unimaginative as far as big bank misdeeds are concerned.

Here is another howler, from a speech in September last year:

But sadly, Breuer’s resignation is unlikely to be a bellwether that lying does not pay. He simply didn’t lie well enough and that made him an embarrassment.

Update: As readers pointed out in comments, and as the article that in the Washington Post indicates, Breuer was also under attack from the right for “Fast and Furious.” So while his departure was likely in the cards, the fact that it was leaked so closely after his embarrassing Frontline performance (clearly understood to be embarrassing by virtue of the sharp reaction from the DoJ) suggests that it was leaked now so as to head off calls for his resignation or other forms of criticism. Why get worked up about a lame duck?

Here is another howler, from a speech in September last year:

One of the reasons why deferred prosecution agreements are such a powerful tool is that, in many ways, a DPA has the same punitive, deterrent, and rehabilitative effect as a guilty plea: when a company enters into a DPA with the government, or an NPA for that matter, it almost always must acknowledge wrongdoing, agree to cooperate with the government’s investigation, pay a fine, agree to improve its compliance program, and agree to face prosecution if it fails to satisfy the terms of the agreement. All of these components of DPAs are critical for accountability.Huh? Notice no mention of indictment? The mere threat of indictment got Hank Greenberg, one of the most litigious and tenacious people on the planet, forced out of AIG pronto. That’s because an indictment is a death knell to a levered financial firm. Many customers and counterparties have to stop dealing with it immediately. That does not mean this weapon should be used casually. But the key element is not to destroy viable businesses through a prosecution, but to punish executives. There are ways to be far more aggressive and imaginative (for instance, under Sarbanes Oxley, the language for criminal violations tracks the language for civil violations’; a successful civil case could lay the groundwork for the related criminal action). But you’d never see that from Breuer, who as Marcy Wheeler pointed out,uncritically accepted presentations by economists hired by miscreant institutions who warned that indicting their client would be Too Terrible To Contemplate.

But sadly, Breuer’s resignation is unlikely to be a bellwether that lying does not pay. He simply didn’t lie well enough and that made him an embarrassment.

Update: As readers pointed out in comments, and as the article that in the Washington Post indicates, Breuer was also under attack from the right for “Fast and Furious.” So while his departure was likely in the cards, the fact that it was leaked so closely after his embarrassing Frontline performance (clearly understood to be embarrassing by virtue of the sharp reaction from the DoJ) suggests that it was leaked now so as to head off calls for his resignation or other forms of criticism. Why get worked up about a lame duck?

Read more at http://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2013/01/for-once-maybe-lying-does-not-pay-dojs-lanny-breuer-resigns-abruptly-after-frontline-appearance.html#BwcvGUqEXyvOFJkb.99

http://www.zerohedge.com/news/2013-01-23/assistant-attorney-general-breuer-leave-doj-untouchables-aftermath

Assistant Attorney General Breuer Out Of DOJ In "Untouchables" Aftermath

Submitted by Tyler Durden on 01/23/2013 18:11 -0500

and the prior story.... where Mr B made the mistake of spreading too much truth , much too transparently - and not on a summer Friday night news dump but right during the middle of the day !

http://www.zerohedge.com/news/2013-01-23/assistant-attorney-general-admits-tv-us-justice-does-not-apply-banks

Earlier today, we reported that "Assistant Attorney General Admits On TV That In The US Justice Does Not Apply To The Banks" when we commented on last night's PBS special "The Untouchables." Explicitly, we said that it was "Lenny Breuer who made it very clear that when it comes to the concept of justice the banks are and always have been "more equal" than others. He does so in such shocking clarity and enthusiasm that it is a miracle that this person is still employed by the US Department of Justice." As of minutes ago that is no longer the case as his employment contract has been torn up. TheWaPo reports, that Lanny A. Breuer is leaving the Justice Department "after leading the agency’s efforts to clamp down on public corruption and financial fraud at the nation’s largest banks, according to several people familiar with the matter....It is not clear when Breuer intends to leave, nor what he plans to do once he departs, but it is certain that the prosecutor’s days in office are winding down, according to people who were not authorized to speak publicly about the matter."

Breuer is widely credited with aggressively going after white-collar crime in the aftermath of the crisis. He also stepped up the division’s involvement in money laundering cases, launching a series of criminal investigations that have resulted in multimillion-dollar settlements....Critics have also decried Breuer’s routine use of deferred prosecution, which gives the agency the right to go after a company in the future if it fails to comply with the terms of the agreement. They say the use of such tactics amounts to a slap on the wrists of companies that have engaged in egregious behavior. Breuer, however, has argued that the agreements result in greater accountability for corporate wrongdoing.

Or none, as the case may be.

Brauer is not only known for being the bankers' lackey: his fingerprints are also all over Fast and Furious:

During Senate hearings in 2011, Breuer admitted that he failed to alert other Justice Department officials that federal agents had allowed guns to illegally flow into Mexico and onto U.S. streets between 2006 and 2007. The practice, known as “gun walking,” was also a key part of the Obama administration’s Phoenix gun trafficking operation, Fast and Furious.The operation came under fire when many of the weapons later turned up at crime scenes in Mexico and the United States, including two where a U.S. Border Patrol agent was killed.Several officials at the Justice Department resigned in connection with the operation, including Jason Weinstein, a deputy assistant attorney general in the criminal division. Breuer later apologized for his inaction, when the tactics first came to his attention. Sen. Charles E. Grassely (R-Iowa) called for his resignation, but Attorney General Eric H. Holder Jr. stood behind Breuer.As one of the longest-serving heads of the criminal division, Breuer’s tenure has been filled with controversy and high-profile prosecutions. He was admonished for his role in the agency’s botched attempt to infiltrate weapon-smuggling rings in the operation dubbed Fast and Furious. And he has been accused of being soft on Wall Street for failing to throw senior bank executives behind bars for their role in the financial crisis.

Either way, Brauer is gone.

And ironically it is his departure which confirms that everything that could be wrong at the US department of INjustice, is wrong.

Because, with all due respect to this banker muppet, he is merely the tiniest cog in a broken down judicial system, which works (and we obviously use the term loosely) in conjunction with the legislative and executive branches, as well as that implied fourth branch - the Federal Reserve - to further just one thing: the interests of the bankster overclass, who ever since the financial crisis have benefited to the tune of some $5 trillion, or the full amount of incurred debt that future generations of Americans will be responsible for, and yet which benefit primarily the financial oligarch right here and right now.

Fixing the unprecedented level of corruption that has gripped America will not be done with the voluntary retirement of one person who should have done more, but kept his mouth shut (for whatever selfish reasons). The system, sadly, is so rotten to the core, that only a grand reset of every social and political institution will help.

Luckily, we have the Fed for that, which courtesy of its lunatic actions is bringing this once great country every day closer to the abyss.

The good news: there is no turning back now - the entire financial system is now on crash course at a pace of $85 billion per month and accelerating.

The bad news: it will take a while before the final tide subsides for one final time as the status quo will certainly not go without a fight. A very big, and very lethal fight.

and the prior story.... where Mr B made the mistake of spreading too much truth , much too transparently - and not on a summer Friday night news dump but right during the middle of the day !

http://www.zerohedge.com/news/2013-01-23/assistant-attorney-general-admits-tv-us-justice-does-not-apply-banks

Assistant Attorney General Admits On TV That In The US Justice Does Not Apply To The Banks

Submitted by Tyler Durden on 01/23/2013 10:59 -0500

- Bill Gross

- Corruption

- Counterparties

- Department of Justice

- Hank Paulson

- Hank Paulson

- Kaufman

- Mutual Assured Destruction

- President Obama

- Ted Kaufman

- White House

Those who watched Frontline's special on why nobody has been prosecuted on Wall Street titled appropriately "The Untouchables" didn't learn much new. The rehash of ideas presented is what has been well known for years - namely that when it comes to prosecuting Wall Street criminals nothing will ever happen, because as Bill Gross tweeted "Its not Republican in politics. Its not Dem in politics. Its money in politics" and all the money in politics comes from Wall Street, which happens to be the ultimate ruler of the United States of America, pushing levers here and pulling stringer there to give the impression the constitutional republic is still alive. It isn't - this country has become an unchecked despotism of those in charge of money creation and who control capital - just the thing Andrew Jackson warned against. One thing we did learn, was courtesy of Assistant Attorney General Lenny Breuer who made it very clear that when it comes to the concept of justice the banks are and always have been "more equal" than others. He does so in such shocking clarity and enthusiasm that it is a miracle that this person is still employed by the US Department of Justice.

To wit from the transcript:

MARTIN SMITH: You gave a speech before the New York Bar Association. And in that speech, you made a reference to losing sleep at night, worrying about what a lawsuit might result in at a large financial institution.LANNY BREUER: Right.MARTIN SMITH: Is that really the job of a prosecutor, to worry about anything other than simply pursuing justice?LANNY BREUER: Well, I think I am pursuing justice. And I think the entire responsibility of the department is to pursue justice.But in any given case, I think I and prosecutors around the country, being responsible, should speak to regulators, should speak to experts, because if I bring a case against institution A, and as a result of bringing that case, there’s some huge economic effect — if it creates a ripple effect so that suddenly, counterparties and other financial institutions or other companies that had nothing to do with this are affected badly — it’s a factor we need to know and understand.

In other words, no criminal charges can be levied against anyone who engaged in the crimes leading to the great financial crisis of 2008 because, get this, the implications of pursuing justice may have destabilizing implications!

In other words, the banker threat of Mutual Assured Destruction has metastasized from the legislative, where in 2008 Hank Paulson demanded a blank check from Congress to spend it on whatever he wishes, "or else...", and has fully taken over the Judicial, where there is Justice for all... and no "Justice" for those who are systemically important.

Ted Kaufman summarizes:

TED KAUFMAN: That was very disturbing to me, very disturbing. That was never raised at any time during any of our discussions.That is not the job of a prosecutor, to worry about the health of the banks, in my opinion. Job of the prosecutors is to prosecute criminal behavior. It’s not to lie awake at night and kind of decide the future of the banks.

Alas Ted, it appears it is.

Frontline's conclusion was perfectly expected: "to date, not one senior Wall Street executive has been held

criminally liable by the Department of Justice for activities related to

the financial crisis."

criminally liable by the Department of Justice for activities related to

the financial crisis."

We now know why: it is because of people like this:

Lanny A. Breuer was unanimously confirmed as Assistant Attorney General for the Criminal Division on April 20, 2009.

As head of the Criminal Division, Mr. Breuer oversees nearly 600 attorneys who prosecute federal criminal cases across the country and help develop the criminal law. He also works closely with the nation’s 94 U.S. Attorneys’ Offices in connection with the investigation and prosecution of criminal matters in their districts. Mr. Breuer is a national leader on a range of federal law enforcement priorities, including financial fraud, health care fraud, public corruption, and violence along the Southwest Border. He has also been a leading voice on policy issues related to criminal law enforcement, including the scope of prosecutors’ discovery obligations in federal criminal cases and sentencing disparities between crack and powder cocaine offenses. Mr. Breuer regularly testifies before Congress on the Administration’s policy initiatives and advises the Attorney General and the White House on matters of criminal law. Mr. Breuer also serves as the Department's representative on the Atrocities Prevention Board, which President Obama announced in April 2012. For his work as Assistant Attorney General, the National Law Journal named Mr. Breuer a "Visionary" in the Washington, D.C. legal community, and he was recently ranked sixth on Ethisphere’s list of The 100 Most Influential People in Business Ethics.

Mr. Breuer began his legal career in 1985 as an Assistant District Attorney in Manhattan, where he prosecuted violent crime, such as armed robbery and gang violence, white collar crime, and other offenses. In 1989, he joined the law firm of Covington & Burling LLP, where he worked until 1997, when he joined the White House Counsel’s Office as Special Counsel to President William Jefferson Clinton. As Special Counsel, Mr. Breuer assisted in defending President Clinton in the Senate impeachment trial.Mr. Breuer returned to Covington in 1999 as co-chair of the White Collar Defense and Investigations practice group, where he specialized in white collar criminal defense and complex civil litigation and represented individuals and corporations in matters involving high-stakes legal risks. He also vice-chaired the firm’s Public Service Committee. At Covington, Mr. Breuer developed a reputation as one of the top defense lawyers in the country.

No comments:

Post a Comment